The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the lives of the nation’s estimated 62.7 million parents with children under age 18 as access to paid, unpaid or subsidized child care and school supervision ended for many. The recent end of pandemic relief funds may continue the disruptions for some households, potentially affecting availability of child care for years to come.

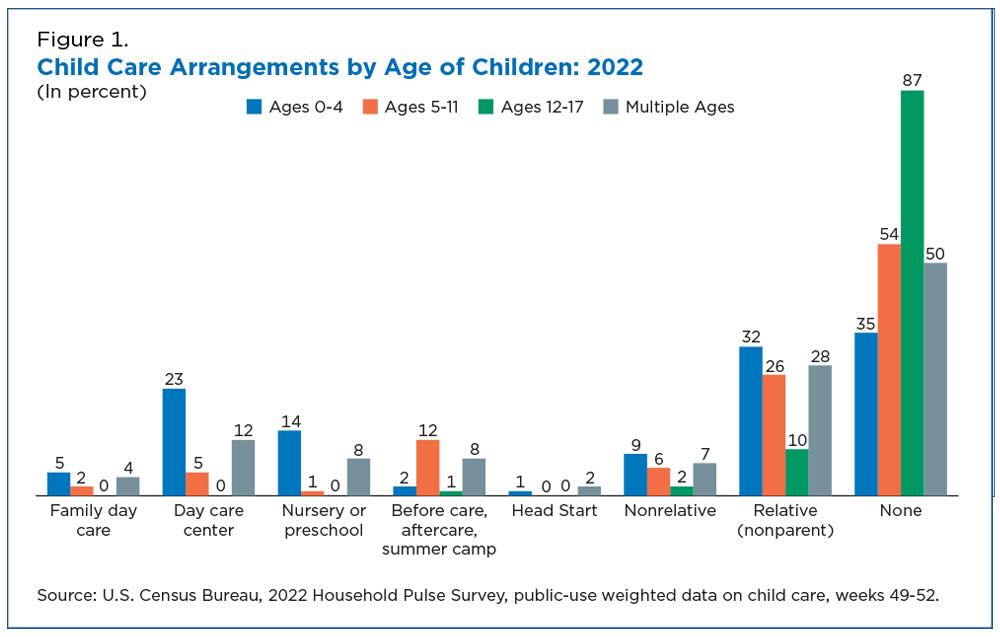

Interestingly, most parents regardless of their kids’ ages, said they didn’t have any type of child care arrangement, including 35% of those with children under age 5 and more than half (54%) with children ages 5 to 11.], according to U.S. Census.

Now that the pandemic emergency has ended, schools have reopened and child care services are more widely available again, how are parents — especially the 50.7 million parents in the labor force — handling the care of their children?

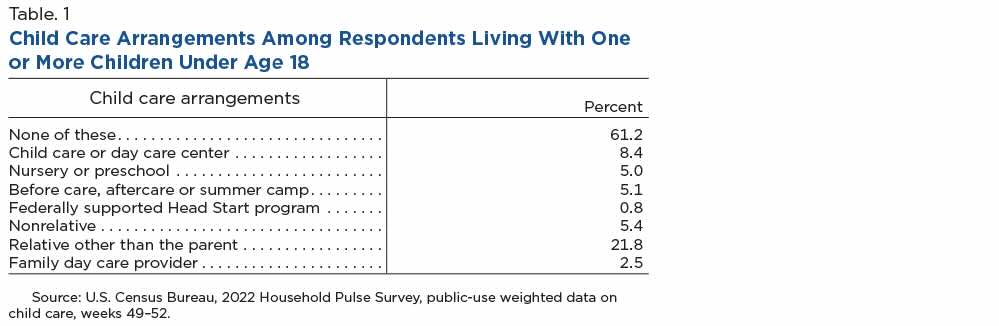

When asked in the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) from September to December 2022, roughly 61% of parents living with at least one child age 17 or younger said they did not have any formal child care arrangements. The survey shows that:

About 1 in 5 (21.8%) reported child care was provided by a relative other than a parent.

Around 8.4% reported using a day care center.

About 5% reported using one of the following options: nonrelative care (5.4%); nursery or preschool (5.4%); or before/after school care (5.1%).

About 3% used a family day care.

Only 1% reported participating in the Head Start program.

HPS and Child Care

In September of 2022, the HPS introduced new questions about types and costs of child care arrangements (Table 1).

In this article we focus on child care arrangements by the ages of children, employment of parents and household income.

Respondents were asked which child care arrangements they had used in the past seven days to look after the children in the household. Parents could select all the options applicable to them.

If they chose “none of these,” they were prevented from selecting any of the substantive categories of types of care. As Table 1 shows, 61.2% selected “none.” The remaining 38.8% were enabled to select “all that apply” among the substantive categories (thus, overall percentages add to more than 100).

Types of Child Care and No Child Care

Types of child care arrangements used by parents varied according to the age of the children (Figure 1).

Parents who reported not having any type of child care arrangement may have selected this response to describe a variety of circumstances, such as having a stay-at-home parent care for children, being unable to access care for their young children or having children old enough to care for themselves.

Interestingly, most parents regardless of their kids’ ages, said they didn’t have any type of child care arrangement, including 35% of those with children under age 5 and more than half (54%) with children ages 5 to 11.

Parents might be caring for children while also working or in school given the difficulties of finding affordable child care and the shift to remote work. In addition, many households made the difficult choice of having one parent, usually women, drop out of the labor force and stay home to care for children.

Child Care Arrangements and Employment

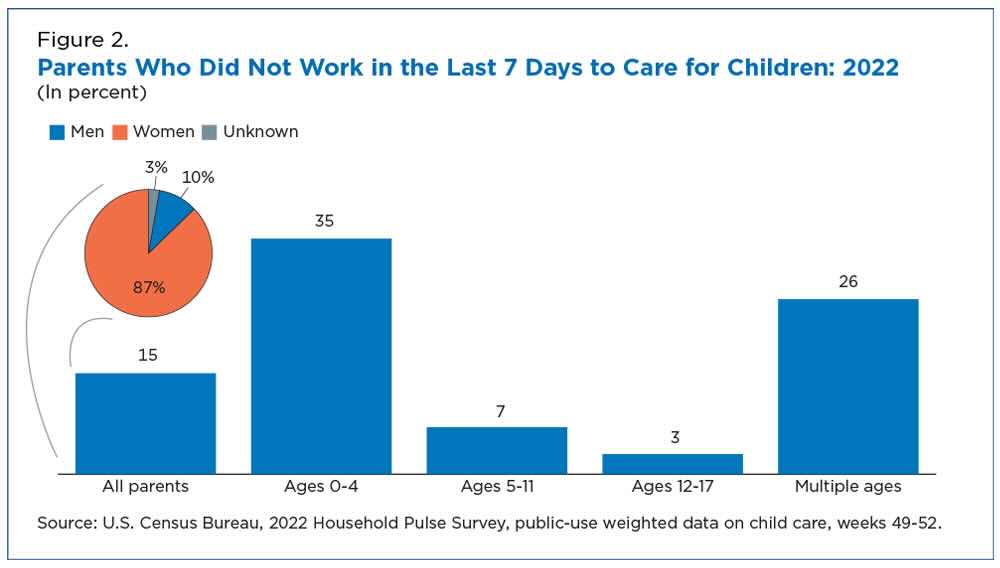

Lack of child care impacted parents’ employment (Figure 2).

Around 15% of parents who had not worked in the last seven days reported they were unemployed in order to provide care to their children who weren’t in school or day care. This trend was particularly pronounced among parents of young children, with more than a third (35%) reporting they didn’t work because they needed to care for them.

The responsibility of providing care for these children was overwhelmingly borne by mothers: nearly 9 out of 10 parents (87%) who did not work to care for children were women.

Child Care Arrangements and Income

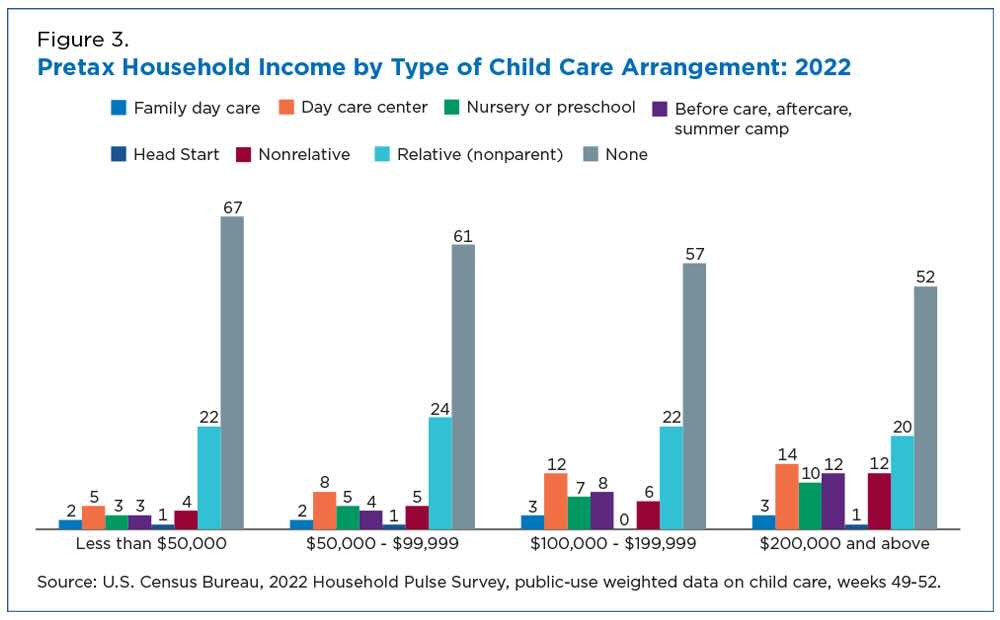

Income also had a notable impact on the type of child care arrangement families used (Figure 3).

Lower income households were most likely not to have any type of child care arrangement: 67% with annual household incomes under $50,000 reported not having child care compared to 52% of households earning more than $200,000 a year.

Approximately one-fifth of parents relied on a relative for child care, regardless of household income, but as household income increased so did use of daycare centers, preschools, and before and aftercare.

The Trade Off: Child Care and Employment

Parents of young children must weigh factors like cost and availability of child care when determining whether to work outside the home. Lower income families may struggle to access quality child care and in some cases, the cost of such care may exceed the income generated by the working parent. When one parent is unable to work due to child care needs, the responsibility tends to fall on women.

While these struggles predate the COVID-19 pandemic, the pandemic likely exacerbated the challenges that families with young children face when arranging for child care. Although schools and day care centers have reopened, lack of child care disproportionally affects employment opportunities for parents of young children, particularly women.

\The HPS provides near real-time data on the impact of social and economic factors like employment status, food security, and housing security on Americans’ lives. Information on the methodology and reliability of these estimates can be found in the source and accuracy statements for each data release.

Data users interested in state-level sample sizes, the number of respondents, weighted response rates and occupied housing unit coverage ratios can consult the quality measures file available at the same location.

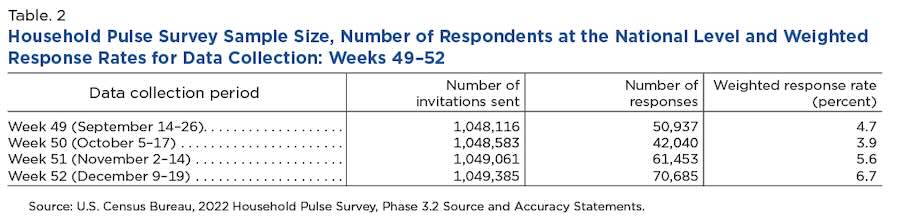

These data were collected over five weeks in 2022 from September 14 to December 19 of the survey, which was sent to more than 1 million adults in households each month (Table 2).

Authors:

Casey Eggleston is a survey methodologist in the Census Bureau’s Center for Behavioral Science Methods.

Yerís H. Mayol-García is a sociologist and demographer in the Census Bureau’s Fertility and Family Statistics Branch.

Mikelyn Meyers is the Senior coordinator for decennial research in the Census Bureau’s Center for Behavioral Science Methods.

Yazmin Garcia Trejo is chief of the Response and Measurement Branch in the Census Bureau’s Decennial Statistics Studies Division.

Discussion about this post