powerful new tool for discovering planets outside of the solar system has officially started its scientific mission. NEID is a state-of-the-art spectrometer that collected its preliminary “first light” in early 2020 and now, after some delays due to the pandemic, is fully operational.

High-precision exoplanet detection

According to University of Pennsylvania, as part of a joint NSF and NASA program, NEID’s mission is to use high-precision measurements to detect and discover new exoplanets. The spectrometer was built under an aggressive construction timeline by a team of scientists, including Cullen Blake, Penn associate professor and NEID instrument scientist, and installed at the WIYN 3.5m telescope at Kitt Peak in 2019. In consulation with the Tohono O’odham Nation, the NEID spectrometer’s name is derived from the Tohono O’odham word meaning “to see.”

After its installation and subsequent “first light,” the instrument had to complete a testing phase to demonstrate that it performed to specification. NEID has now completed its operational readiness review and is ready to collect data. A trove of NEID observations of the sun that were collected as part of the testing phase has also been released to the public, data that will be extremely valuable to astronomers about how the behavior of a star could conceal or mimic the tiny signal from a genuine exoplanet.

“For decades, the iconic and now decommissioned McMath Pierce telescope at Kitt Peak was the premier facility for studying the sun,” says Suvrath Mahadevan, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Pennsylvania State University and principal investigator of NEID. “NEID is now the bridge that connects exoplanet science to solar observations, the sun to the stars, and a bridge that connects Kitt Peak’s history to its present and future.”

NEID works by measuring the minute gravitational tug, known as a “wobble,” of exoplanets against their host star. Earth’s pull against the sun, for example, causes the sun to wobble with a speed of 10 cm per second, a scale that was challenging to detect with previous exoplanet-detecting devices. “For a long time, the state-of-the-art was about 1 meter per second, so about 10 times worse than the signal from Earth orbiting the Sun,” says Blake. “Now, with NEID, that resolution is about 20-30 cm per second.”

NEID joins a number of new state-of-the-art planet-hunting devices and surveys around the world, whose goal is to detect “twins” to Earth, planets of a similar size and that are not located too far away from or too close to the host star. NEID’s spectrometer is also able to detect Earthlike-planets that orbit stars smaller than the sun or have a shorter orbital period than Earth thanks to the device’s increased sensitivity.

This improved precision only allows researchers to spot previously undectable exoplanets and helps astronomers more accurately interpret some of the complex star behaviors. This stellar activity, caused by convection, sunspots, and solar flares, can produce signals that masquerade as possible exoplanets. “Stars have a lot of behaviors and characteristics on a number of time scales, from minutes and hours to years, and a big frontier has been disentangling what stars do from what planets do. The extra precision is helpful in that regard,” says Blake.

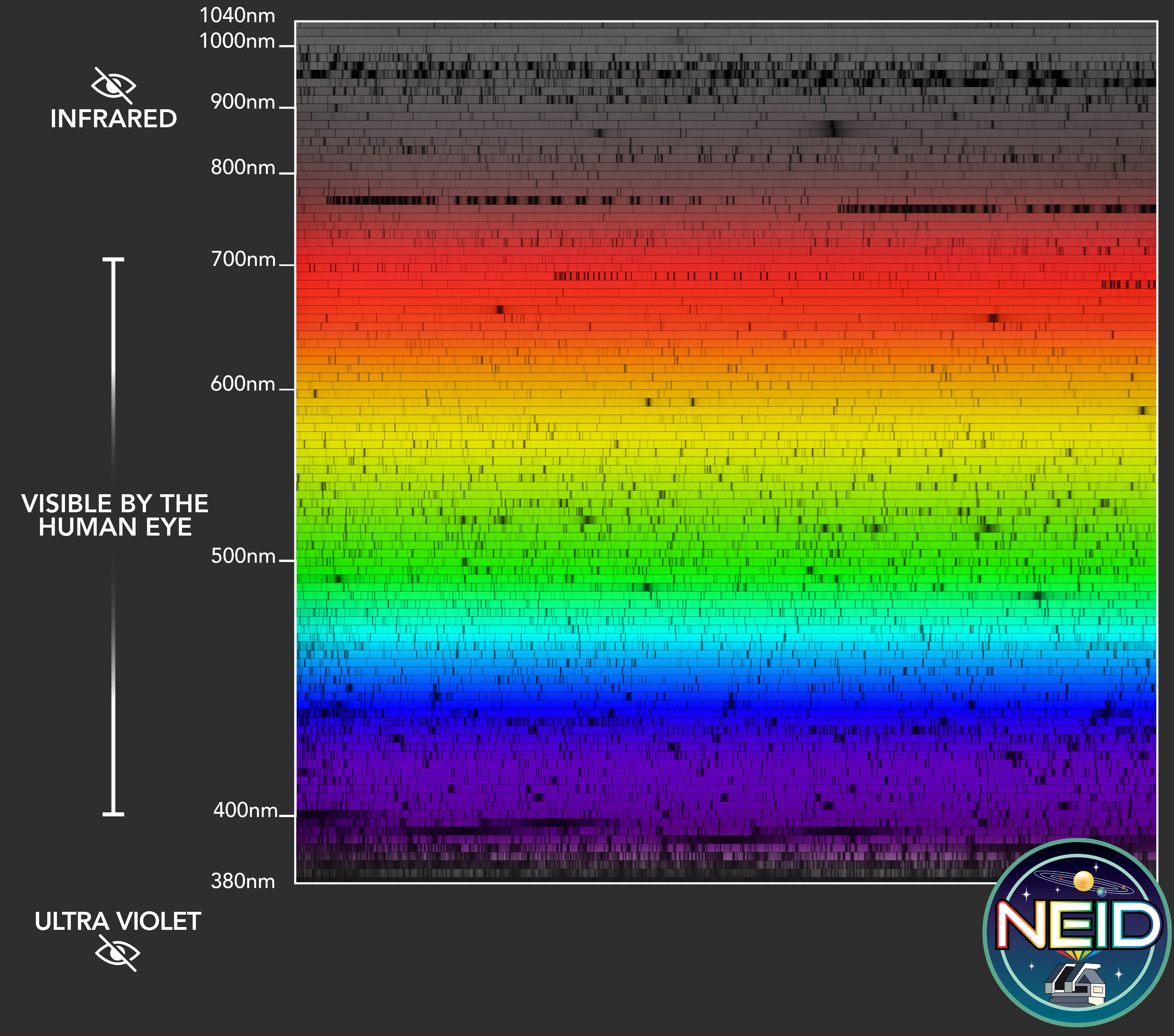

An image of NEID’ spectroscopic observations of the Sun. NEID’s spectral coverage extends significantly redder and bluer than the limits of human vision, enabling it to observe many critical spectral lines. NEID’s design enables high spectral resolution, large wavelength coverage, and exquisite stability. (Image: Dani Zemba, Guðmundur Stefánsson, and the NEID Team)

Looking up while looking ahead

“NEID has been the incredible story of a team that has delivered, in record time of a little over four years that include seven months of stoppage for COVID and then working through the height of this pandemic, an instrument that sets a new standard and will produce breakthrough science,” says WIYN Executive Director Jayadev Rajagopal.

Now that NEID is fully operational, NSF and NASA are accepting proposals from the astronomy community to use part of the allotted 120 nights of observation time each year. As part of the team that built NEID, Blake’s research group has access to observations from guaranteed time, and one project that Blake is eager to get started on is an intensive study of nearby, “well-behaved” bright stars around which they will be looking for as-of-yet undetected planets.

“There’s a huge number of proposals, with lots of really interesting stuff—even some outside of the box sorts of things. It will be really exciting to see what all that will produce,” Blake says. “At the same time, it’s almost always the case that when new instruments and capabilities come online, it’s the stuff that someone hadn’t thought of that can end up being really exciting.”

by Erica K. Brockmeier

Discussion about this post