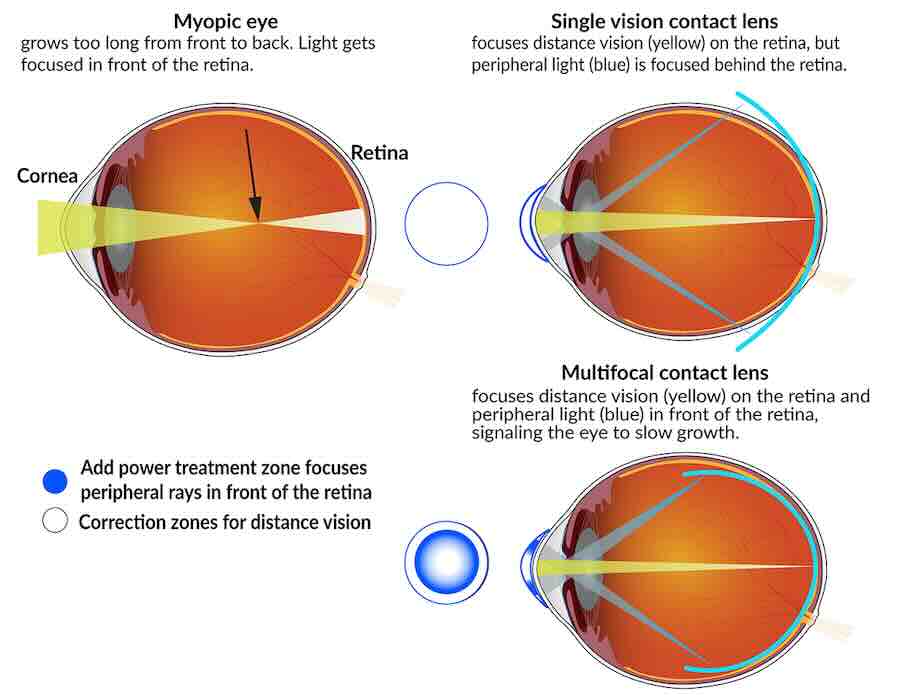

A myopic eye grows too long from front to back. Light gets focused in front of the retina. Single-vision contact lenses focus distance vision on the retina, but peripheral light is focused behind the retina. Multifocal contact lenses focus distance visionA myopic eye grows too long from front to back. Light gets focused in front of the retina. NEI

In a follow up study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), researchers found that children who wore special contact lenses to slow progression of nearsightedness, known as myopia, maintained the treatment benefit after they stopped wearing the contacts as older teens. Controlling myopia progression in childhood can help to potentially decrease the risks of vision-threatening myopia complications later in life, such as retinal detachment and glaucoma. Rates of myopia have been increasing in recent years with some implications that higher use of personal devices plays a role.

Myopia occurs when a child’s developing eyes grow too long from front to back. Instead of focusing images directly on the retina—the light-sensitive tissue in the back of the eye—images of distant objects are focused at a point in front of the retina. As a result, people with myopia have good near vision but poor distance vision.

“There was concern that the eye might grow faster than normal when myopia-control contact lenses were discontinued. Our findings show that when older teenagers stopped wearing these lenses, the eye returned to the age-expected rate of growth,” said principal investigator, David A. Berntsen, O.D., Ph.D., chair of clinical sciences at the University of Houston College of Optometry.

The new study follows an original clinical trial that showed soft contact lenses designed to add high focusing power to one’s peripheral vision, as well as correction for one’s distance vision, were most effective at slowing the rate of eye growth, decreasing how myopic children became. Participants in the follow up study wore high-add lenses for two years, followed by single-vision contact lenses for the third year of the study to see if the benefit remained after discontinuing treatment.

At the end of the follow up study, axial eye growth returned to age-expected rates. While there was a small increase (0.03 mm/year) in eye growth across all age groups after discontinuing multifocal lenses, the overall rate of eye growth was no different than the age expected rate.

Participants who had been in the original study high-add multifocal treatment group continued to have shorter eyes and less myopia at the end of the follow-up study. Children who were switched to high-add multifocal contact lenses for the first time during the follow-up study did not catch up to those who had worn high-add lenses since the start of the original clinical trial when they were 7 to 11 years of age.

“Our findings suggest that it’s a reasonable strategy to fit children with multifocal contact lenses for myopia control at a younger age and continue treatment until the late teenage years when myopia progression has slowed,” said follow-up study chair, Jeffrey J. Walline, O.D., Ph.D., associate dean for research at the Ohio State University College of Optometry, Columbus.

Single vision prescription glasses and contact lenses can correct myopic vision, but they fail to treat the underlying problem, which is the eye continuing to grow longer than normal. By contrast, soft multifocal contact lenses correct myopic vision in children while simultaneously slowing myopia progression by slowing eye growth.

Designed like a bullseye, multifocal contact lenses focus light in two basic ways. The center portion of the lens corrects nearsightedness so that distance vision is clear, and it focuses light directly on the retina. The outer portion of the lens adds focusing power to bring the peripheral light into focus in front of the retina. Animal studies show that bringing light to focus in front of the retina may slow growth. The higher the reading power, the further in front of the retina it focuses peripheral light.

In the original study, 294 myopic children, ages 7 to 11 years, were randomly assigned to wear single vision contact lenses or multifocal lenses with either high-add power (+2.50 diopters) or medium-add power (+1.50 diopters). They wore the lenses during the day as often as they could comfortably do so for three years.

After three years in the original study, children in the high-add multifocal contact lens group had shorter eyes compared to the medium-add power and single-vision groups, and they also had the slowest rate of myopia progression and eye growth.

The study, known as the Bifocal Lenses In Nearsighted Kids (BLINK), and follow-on study, known as BLINK2 published their findings today in JAMA Ophthalmology. The study was funded by NIH’s National Eye Institute (NEI).

Discussion about this post