With TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube on the rise, we look at why consumers are embracing more video consumption and investigate which mainstream and alternative accounts – including creators and influencers – are getting most attention when it comes to news. Authors of the report explore the very different levels of confidence people have in their ability to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy content on a range of popular third-party platforms around the world. For the first time in our survey. As publishers rapidly adopt AI, to make their businesses more efficient and to personalise content, our research suggests they need to proceed with caution, as the public generally wants humans in the driving seat at all times.

In many countries, especially outside Europe and the United States, researchers found a significant further decline in the use of Facebook for news and a growing reliance on a range of alternatives including private messaging apps and video networks. Facebook news consumption is down 4 percentage points, across all countries, in the last year.

News use across online platforms is fragmenting, with six networks now reaching at least 10% of our respondents, compared with just two a decade ago. YouTube is used for news by almost a third (31%) of our global sample each week, WhatsApp by around a fifth (21%), while TikTok (13%) has overtaken Twitter (10%), now rebranded X, for the first time.

Linked to these shifts, video is becoming a more important source of online news, especially with younger groups. Short news videos are accessed by two-thirds (66%) of our sample each week, with longer formats attracting around half (51%). The main locus of news video consumption is online platforms (72%) rather than publisher websites (22%), increasing the challenges around monetisation and connection.

Although the platform mix is shifting, the majority continue to identify platforms including social media, search, or aggregators as their main gateway to online news. Across markets, only around a fifth of respondents (22%) identify news websites or apps as their main source of online news – that’s down 10 percentage points on 2018. Publishers in a few Northern European markets have managed to buck this trend, but younger groups everywhere are showing a weaker connection with news brands than they did in the past.

Turning to the sources that people pay most attention to when it comes to news on various platforms, we find an increasing focus on partisan commentators, influencers, and young news creators, especially on YouTube and TikTok. But in social networks such as Facebook and X, traditional news brands and journalists still tend to play a prominent role.

Concern about what is real and what is fake on the internet when it comes to online news has risen by 3 percentage points in the last year with around six in ten (59%) saying they are concerned. The figure is considerably higher in South Africa (81%) and the United States (72%), both countries that have been holding elections this year.

Worries about how to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy content in online platforms is highest for TikTok and X when compared with other online networks. Both platforms have hosted misinformation or conspiracies around stories such as the war in Gaza, and the Princess of Wales’s health, as well as so-called ‘deep fake’ pictures and videos.

As publishers embrace the use of AI we find widespread suspicion about how it might be used, especially for ‘hard’ news stories such as politics or war. There is more comfort with the use of AI in behind-the-scenes tasks such as transcription and translation; in supporting rather than replacing journalists.

Trust in the news (40%) has remained stable over the last year, but is still four points lower overall than it was at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic. Finland remains the country with the highest levels of overall trust (69%), while Greece (23%) and Hungary (23%) have the lowest levels, amid concerns about undue political and business influence over the media.

Elections have increased interest in the news in a few countries, including the United States (+3), but the overall trend remains downward. Interest in news in Argentina, for example, has fallen from 77% in 2017 to 45% today. In the United Kingdom interest in news has almost halved since 2015. In both countries the change is mirrored by a similar decline in interest in politics.

At the same time, we find a rise in selective news avoidance. Around four in ten (39%) now say they sometimes or often avoid the news – up 3 percentage points on last year’s average – with more significant increases in Brazil, Spain, Germany, and Finland. Open comments suggest that the intractable conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East may have had some impact. In a separate question, we find that the proportion that say they feel ‘overloaded’ by the amount of news these days has grown substantially (+11pp) since 2019 when we last asked this question.

In exploring user needs around news, our data suggest that publishers may be focusing too much on updating people on top news stories and not spending enough time providing different perspectives on issues or reporting stories that can provide a basis for occasional optimism. In terms of topics, we find that audiences feel mostly well served by political and sports news but there are gaps around local news in some countries, as well as health and education news.

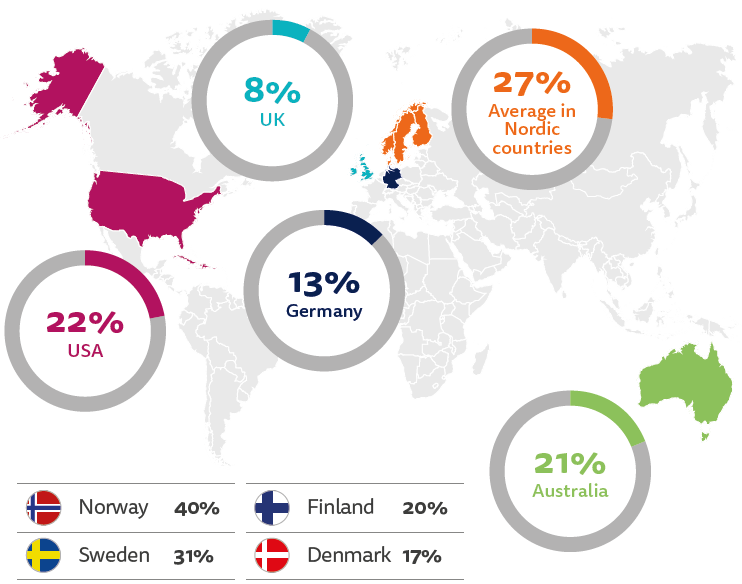

New data show little growth in news subscription, with just 17% saying they paid for any online news in the last year, across a basket of 20 richer countries. North European countries such as Norway (40%) and Sweden (31%) have the highest proportion of those paying, with Japan (9%) and the United Kingdom (8%) amongst the lowest. As in previous years, we find that a large proportion of digital subscriptions go to just a few upmarket national brands – reinforcing the winner-takes-most dynamics that are often linked with digital media.

In some countries we find evidence of heavy discounting, with around four in ten (41%) saying they currently pay less than the full price. Prospects of attracting new subscribers remain limited by a continued reluctance to pay for news, linked to low interest and an abundance of free sources. Well over half (55%) of those that are not currently subscribing say that they would pay nothing for online news, with most of the rest prepared to offer the equivalent of just a few dollars per month, when pressed. Across markets, just 2% of non-payers say that they would pay the equivalent of an average full price subscription.

News podcasting remains a bright spot for publishers, attracting younger, well-educated audiences but is a minority activity overall. Across a basket of 20 countries, just over a third (35%) access a podcast monthly, with 13% accessing a show relating to news and current affairs. Many of the most popular podcasts are now filmed and distributed via video platforms such as YouTube and TikTok.

Online platforms have shaped many aspects of our lives over the last few decades, from how we find and distribute information, how we are advertised to, how we spend our money, how we share experiences, and most recently, how we consume entertainment. But even as online platforms have brought great convenience for consumers – and advertisers have flocked to them – they have also disrupted traditional publishing business models in very profound ways. Our data suggest we are now at the beginning of a technology shift which is bringing a new wave of innovation to the platform environment, presenting challenges for incumbent technology companies, the news industry, and for society.

Platforms have been adjusting strategies in the light of generative AI, and are also navigating changing consumer behaviour, as well as increased regulatory concerns about misinformation and other issues. Meta in particular has been trying to reduce the role of news across Facebook, Instagram, and Threads, and has restricted the algorithmic promotion of political content. The company has also been reducing support for the news industry, not renewing deals worth millions of dollars, and removing its news tab in a number of countries.1

The impact of these changes, some which have been going on for a while, is illustrated by our first chart which uses aggregated data from 12, mostly developed, markets we have been following since 2014. It shows declining, though still substantial, reach for Facebook over time – down 16pp since 2016 – as well as increased fragmentation of attention across multiple networks. A decade ago, only Facebook and YouTube had a reach of more than 10% for news in these countries, now there are many more networks, often being used in combination (several of them are owned by Meta). Taken together, platforms remain as important as ever – but the role and strategy of individual platforms is changing as they compete and evolve, with Facebook becoming less important, and many others becoming relatively more so.

TikTok remains most popular with younger groups and, although its use for any purpose is similar to last year, the proportion using it for news has grown to 13% (+2) across all markets and 23% for 18–24s. These averages hide rapid growth in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia. More than a third now use the network for news every week in Thailand (39%) and Kenya (36%), with a quarter or more accessing it in Indonesia (29%) and Peru (27%). This compares with just 4% in the UK, 3% in Denmark, and 9% in the United States. The future of TikTok remains uncertain in the US following concerns about Chinese influence and it is already banned in India, though similar apps, such as Moj, Chingari, and Josh, are emerging there.

The growing reach of TikTok and other youth-orientated networks has not escaped the attention of politicians who have incorporated it into their media campaigns. Argentina’s new populist president, Javier Milei, runs a successful TikTok account with 2.2m followers while the new Indonesian president, Prabowo Subianto, swept to victory in February using a social media campaign featuring AI-generated images, rebranding the former hard-line general as a cute and charming dancing grandpa. We explore the implications for trust and reliability of information later in this report.

Shift to video networks brings different dynamics

Traditional social networks such as Facebook and Twitter were originally built around the social graph – effectively this means content posted directly by friends and contacts (connected content). But video networks such as YouTube and TikTok are focused more on content that can be posted by anybody – recommended content that does not necessarily come from accounts users have chosen to follow.

Across countries, two-thirds (66%) say they access a short news video, which we defined as a few minutes or less, at least once a week, again with higher levels outside the US and Western Europe. Almost nine in ten of the online population in Thailand (87%), access short-form videos weekly, with half (50%) saying they do this every day. Americans access a little less often (60% weekly and 20% daily), while the British consume the least short-form news (39% weekly and just 9% daily).

Live news streams and long-form recordings are also widely consumed. Taking the United States as an example, we can see how under 35s consume the most of each format, with older people being relatively less likely to consume live or long-form video.

One of the reasons why news video consumption is higher in the United States than in most European countries is the abundant supply of political content from both traditional and non-traditional sources. Some are creators native to online media. Others have come from broadcast backgrounds. In the last few years, a number of high-profile TV anchors, including Megyn Kelly, Tucker Carlson, and Don Lemon, have switched their focus to online platforms as they look to take advantage of changing consumer behaviour.

Carlson’s interview with Russian president Vladimir Putin received more than 200m plays on X and 34m on his YouTube channel. In the UK, another controversial figure, Piers Morgan, recently left his daily broadcast show on Talk TV in favour of the flexibility and control offered as an independent operator working across multiple streaming platforms. (It is worth noting that many of these platform moves came only after the person in question walked out on or were ditched by their former employers on mainstream TV.)

The jury is currently out on whether these big personalities can build robust traffic or sustainable businesses within platform environments. There is a similar challenge for mainstream publishers who find platform-based videos harder to monetise than those consumed via owned and operated websites and apps.

YouTube and Facebook remain the most important platforms for online news video overall (see next chart), but we see significant market differences, with Facebook the most popular for video news in the Philippines, YouTube in South Korea, and X and TikTok playing a key role in Nigeria and Indonesia respectively. YouTube is also the top destination for under 25s, though TikTok and Instagram are not far behind.

Older viewers still like to consume much of their video through news websites, though the majority say they mostly access video via third-party platforms. Only in countries such as Norway do we find that getting on for half of users (45%) say their main video consumption is via websites, a reflection of the strength of brands in that market, a commitment to a good user experience, and a strategy that restricts the number of publisher videos that are posted to platforms like Facebook and YouTube.

Where do people pay attention when using online platforms?

One of the big challenges of the shift to video networks with a younger age profile is that journalists and news organisations are often eclipsed by news creators and other influencers, even when it comes to news.

This year we repeated a question we asked first in 2021 about where audiences pay most attention when it comes to news on various platforms. As in previous years, we find that across markets, while mainstream media and journalists often lead conversations in X and Facebook, they struggle to get as much attention in Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok where alternative sources and personalities, including online influencers and celebrities, are often more prominent.

It is a similar story across many markets, though differences emerge when we look at specific online networks and at a country level. In the following chart we compare attention around news content on YouTube, the second largest network overall. We find that alternative sources and online influencers play a bigger role in both the United States and Brazil than is the case in the United Kingdom.

But who are these personalities and celebrities and what kind of alternative sources are attracting attention? To answer these questions, we asked respondents that had selected each option to list up to three mainstream accounts they followed most closely and then three alternative ones (e.g. alternative accounts, influencers, etc). We then counted and coded these responses.

In the United States, in particular, we find a wide range of politically partisan voices including Tucker Carlson, Alex Jones (recently reinstated on X), Ben Shapiro, Glenn Beck, and many more. These voices come mostly from the right, with a narrative around a ‘trusted’ alternative to what they see as the biassed liberal mainstream media, but there is also significant representation on the progressive left (David Pakman and commentators from Meidas Touch). The top 10 named individuals in the US list are all men who tend to express strong opinions about politics.

Partisan voices (from both left and right) are an important part of the picture elsewhere, but we also find diverse perspectives and new approaches to storytelling. In France, Hugo Travers, 27, known online as Hugo Décrypte, has become a leading news source for young French people for his explanatory videos about politics (2.6m subscribers on YouTube and 5.8m on TikTok). Our data show that across all networks he gets more mentions than traditional news brands such as Le Monde or BFMTV. According to our data, the average audience age of his followers is just 27, compared to between 40 and 45 for large traditional brands such as Le Monde or BFM TV.

Youth-focused brands Brut and Konbini were also widely cited in France, while in the UK, Politics Joe and TLDR News, set up by Jack Kelly, attract attention for videos that try to make serious topics accessible for young people. The most mentioned TikTok news creator in the UK is Dylan Page, who has more than 10m followers on the platform. In the United States, Vitus Spehar presents a fun daily news round-up, often from a prone position on the floor, @underthedesknews (a satirical dig at the classic TV format).

Youth-based news influencers around the world

Coverage of war and conflict

We also found a number of accounts sharing videos about the wars in Gaza and Ukraine. With mainstream news access restricted, young social media influencers in Gaza, Yemen, and elsewhere have been filling in the gaps – documenting the often-brutal realities of life on the ground. Because these videos are posted by many different accounts and ordinary people, it is hard to quantify the impact, but our methodology does pick up a few individual influencer accounts as well as campaigning groups that pull together footage from across social media. As one example, the Instagram account Eye on Palestine appears in our data across a number of countries. The account says it brings ‘the sounds and images that official media does not show’. WarMonitor, one of a number of influential accounts that have been recommended by prominent figures such as Elon Musk, has added hundreds of thousands of followers during the Israel–Palestine conflict.

Finally, celebrities such as Taylor Swift, the Kardashians, and Lionel Messi were widely mentioned by younger people, mostly in reference to Instagram, despite the fact that they rarely talk about politics. This suggests that younger people take a wide view of news, potentially including updates on a singer’s tour dates, on fashion, or on football.

Motivations for using social video

In analysing open comments, we found three core reasons why audiences are attracted to video and other content in social and video platforms.

Fears around AI and misinformation

The last year has seen an increased incidence of so-called ‘deepfakes’, generated by AI including an audio recording falsely purporting to be Joe Biden asking supporters not to vote in a primary, a campaign video containing manipulated photos of Donald Trump, and artificially generated pictures of the war in the Middle East, posted by supporters of both the Palestinian and Israeli sides aimed at winning sympathy for their cause.

AI-generated (fake) pictures from the war have been widely circulated on social media

Research suggests that, while most people do not think they have personally seen these kinds of synthetic images or videos, some younger, heavy users of social media now think they are coming across them regularly.

Journalistic uses of artificial intelligence

News organisations have reported extensively on the development and impact of AI on society, but they are also starting to adopt these technologies themselves for two key reasons. First, they hope that automating behind-the-scenes processes such as transcription, copy-editing, and layout will substantially reduce costs. Secondly, AI technologies could help to personalise the content itself – making it more appealing for audiences. They need to do this without reducing audience trust, which many believe will become an increasingly critical asset in a world of abundant synthetic media.

In the last year, we have seen media companies deploying a range of AI solutions, with varying degrees of human oversight. Nordic publishers, including Schibsted, now include AI-generated ‘bullet points’ at the top of many of their titles’ stories to increase engagement. One German publisher uses an AI robot named Klara Indernach to write more than 5% of its published stories,7 while others have deployed tools such as Midjourney or OpenAI’s Dall-E for automating graphic illustrations. Meanwhile, Digital News Report country pages from Indonesia, South Korea, Slovakia, Taiwan, and Mexico, amongst others, reference a range of experimental chatbots and avatars now presenting the news. Nat is one of three AI-generated news readers from Mexico’s Radio Fórmula, used to deliver breaking news and analysis through its website and across social media channels.8

Nat, one of Radio Fórmula’s AI-generated news readers

Even in countries with relatively strong brands such as the UK, we find significant generational differences when it comes to gateways. Older people are more likely to maintain direct connections, but in the last few years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen both 18–24s and now 25–35s becoming less likely to go directly to a website or app. Across markets we see the same trends with the gap between generations just as significant as country-based differences, if not more.

It is also worth noting the increasing success of mobile aggregators in some countries, many of which are increasingly powered by AI. In the United States, News Break (9%), which was founded by a Chinese tech veteran, has been growing fast with a similar market share to market leader Apple News (11%). In Asian markets, multiple aggregator apps and portals play important gateway and consumption roles, with AI features typically driving ever greater levels of personalisation.

Mobile aggregators tend to be more popular with younger news consumers and are becoming a bigger part of the picture overall, partly fuelled by notifications on relevant topics. In terms of search, there is little evidence that search traffic is drying up and it is certainly not a given that consumers will rush to adopt chatbot interfaces. Even so, publishers expect traffic from search and other gateways to be more unpredictable in the future and will be exploring alternatives with some urgency.

Proportion that paid for any online news in the last year

Selected countries

Via subscription/membership/donation or one-off payment

“In most countries, we continue to see a ‘winner takes most’ market, with a few upmarket national titles scooping up a big proportion of users. In the United States, for example, the New York Times recently announced that it has over 10m subscribers (including 9.9m digital only) while the Washington Post’s numbers have reportedly declined. Having said that, we do find a growing minority of countries where people are paying, on average, for more than one publication, including in the United States, Switzerland, Poland, and France”

This may be because some publishers in these markets are bundling together titles in an all-access subscription (e.g., New York Times, Schibsted, Amedia, Bonnier, Mediahuis). As one example, Amedia’s +Alt product, which offers 100 newspapers, magazines, and podcasts, now accounts for 10% of Norwegian subscriptions, up 6 percentage points this year.

In Nordic countries, it is worth noting the high proportion of local titles being paid for online. In Canada, Ireland, and Switzerland, a significant proportion of subscriptions are going to foreign publishers.

Attention loss, news avoidance, and news fatigue

The long-term trend, however, is down in every country apart from Finland, with high interest halving in some countries over the last decade (UK 70% in 2015; 38% in 2024). Women and young people make up a significant proportion of that decline.

While news interest may have stabilised a bit this year, the proportion that say they selectively avoid the news (sometimes or often) is up by 3pp this year to 39% – a full 10pp higher than it was in 2017. Notable country-based rises this year include Ireland (+10pp), Spain (+8pp), Italy (+7pp), Germany (+5pp), Finland (+5pp), the United States (+5pp), and Denmark (+4pp). The underlying reasons for this have not changed. Selective news avoiders say the news media are often repetitive and boring. Some tell us that the negative nature of the news itself makes them feel anxious and powerless.

Selected news avoidance at highest levels recorded

All markets

Read full report

Discussion about this post