The pandemic saw a large boom in business (or EIN) applications — which translated to comparable percentage increases in establishment openings and entrant job creation — and this increase has remained elevated compared to prepandemic trends.

However, indicators on employer business and entrant job creation are reverting to historical trends, implying that the pandemic surge in business formation has been temporary.

These reversions also imply that future heightened levels of startup activity seem to be a continuation of prepandemic trends rather than the pandemic effect on U.S. entrepreneurial spirits.

Business applications — or applications for employer identification numbers (EINs) — surged at the beginning of the pandemic, more than doubling prepandemic levels of the early 2000s. While not every entrepreneur filing for an EIN is guaranteed to hire workers, this surge in business applications was followed by a strong increase in employer startups more than a year later, as establishment openings rose 45 percent. Interestingly, this rise in employer startups has remained elevated compared to prepandemic levels, although recent evidence indicates that this increase has been wearing off.

In this article, we will argue that the pandemic rise in employer startups was only temporary and future heightened levels of business activity are more likely a continuation of prepandemic trends. Furthermore, we show that most sectors featuring a rise in job creation by startups have experienced almost no productivity growth in the past few years. As a result, it is unlikely that the temporary surge in employer startups has led to significant aggregative productivity gains.

Pandemic Surge in Business Applications and Employers

EIN applications reached a peak of 1.465 million in the third quarter of 2020, an increase of more than 65 percent compared to early 2019 levels. However, many entrepreneurs apply for an EIN with no intention of growing their businesses by hiring employees. For example, entrepreneurs may apply for EINs simply to get business bank accounts (which require EINs).

As a result, the rise in EIN applications could just reflect entrepreneurs becoming self-employed sole proprietors (or “nonemployers”) who don’t heavily affect aggregate productivity growth or job creation. However, this narrative that the rise in business applications were just individuals with side gigs — such as driving Uber or selling homemade art on Etsy — seems to be contradicted by two features of the data.

New Businesses Planning to Have Employees

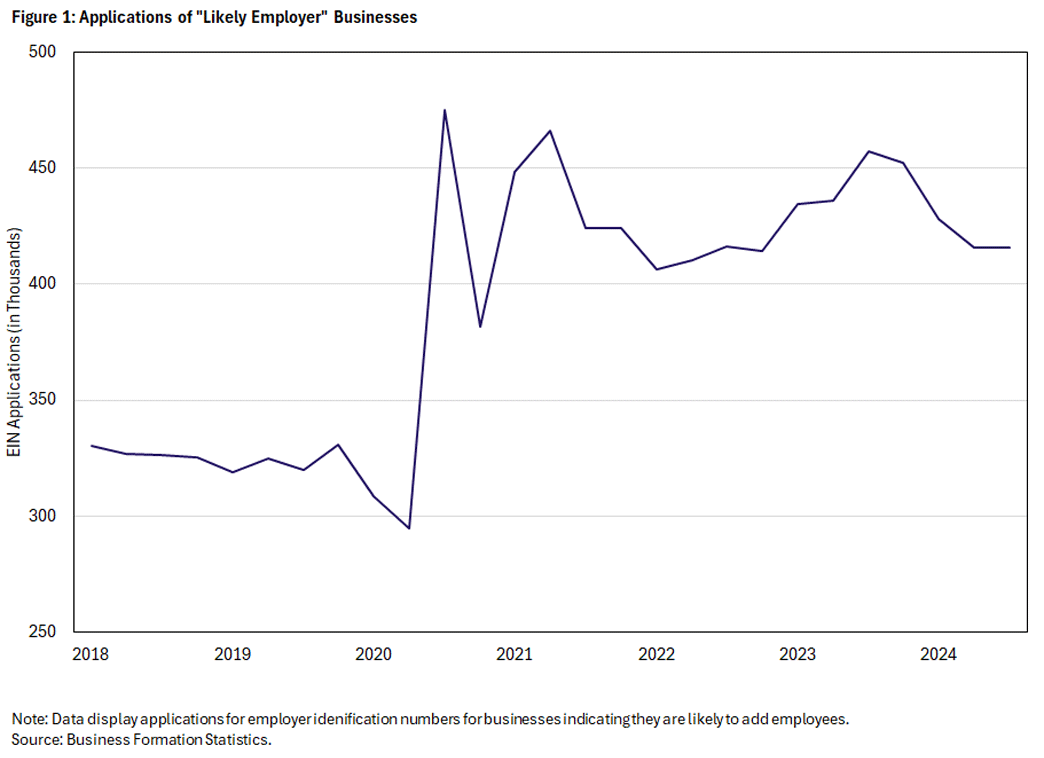

First, Business Formation Statistics (BFS) data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that EIN applications with the intent of hiring employees also surged during the start of the pandemic. These “likely employer” applications peaked in the third quarter of 2020, with an increase of 49 percent relative to 2019, as seen in Figure 1.

New Businesses Creating Jobs

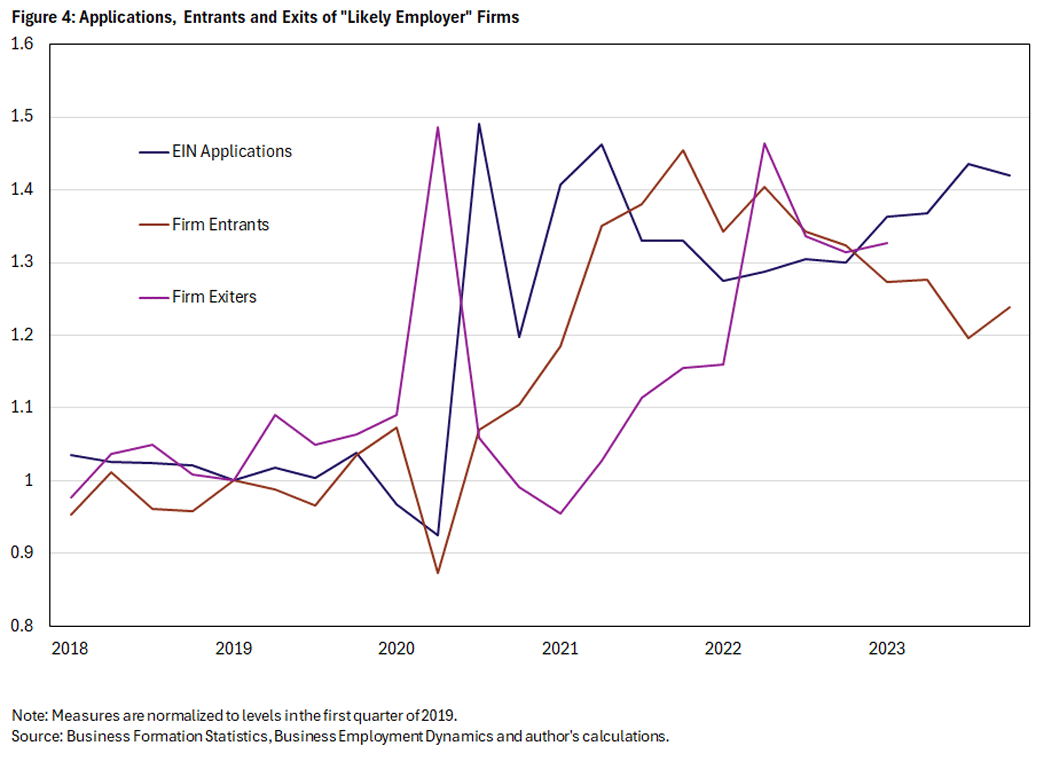

Second, the rise in EIN applications actually translated to a rise in employer establishments and job creation by entrants. According to Business Employment Dynamics (BED) data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), establishment openings (or “entrants”) reached a peak of 378,000 at the end of 2021, almost a full year after the peak in EIN applications. This is an increase of 45 percent compared to prepandemic levels.

Importantly, this surge in the number of establishments was also associated with a peak in job creation by entrants. While the average entrant hired fewer employees than before the pandemic, the total number of jobs created by entrants reached a high of 1.12 million. These are levels that have not been observed in the past 20 years.

Will New Businesses and Their Job Creation Be Sustained?

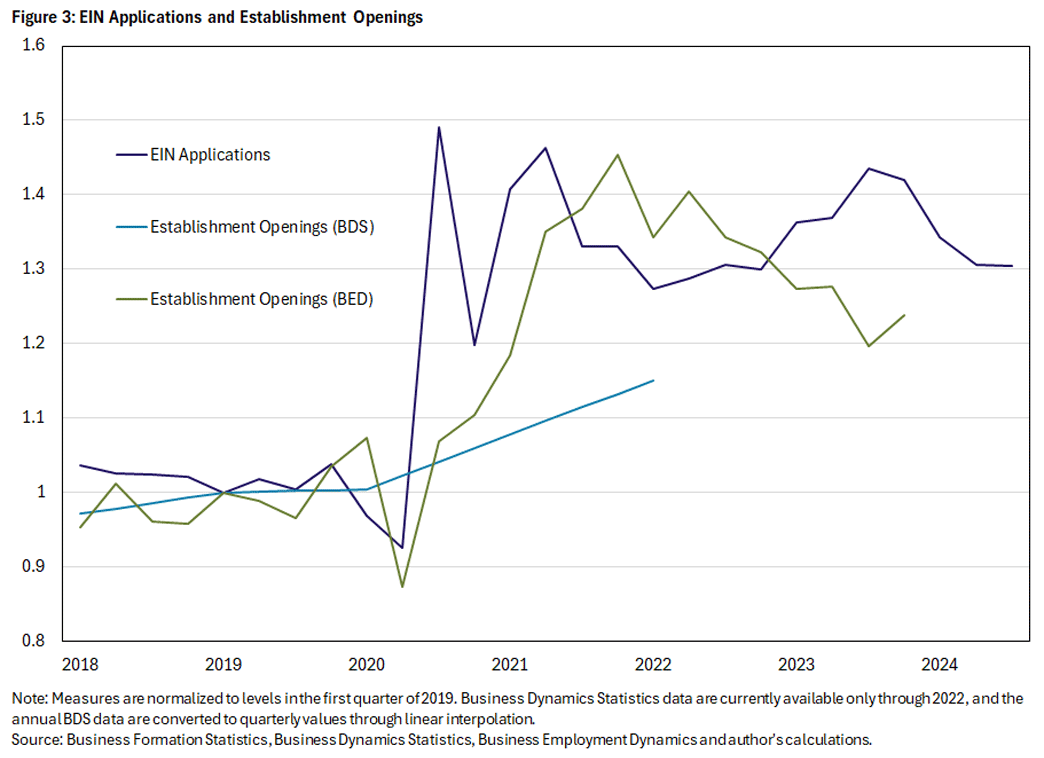

The data clearly indicate that the pandemic stirred American entrepreneurial spirits. The question that follows is whether these heightened levels of establishment openings and entrant job creation can be sustained in the long run. If measures of employer business formation were to keep tracking EIN application patterns (albeit with a delay), then we would expect this to be the case. However, the data appear to paint a different picture.

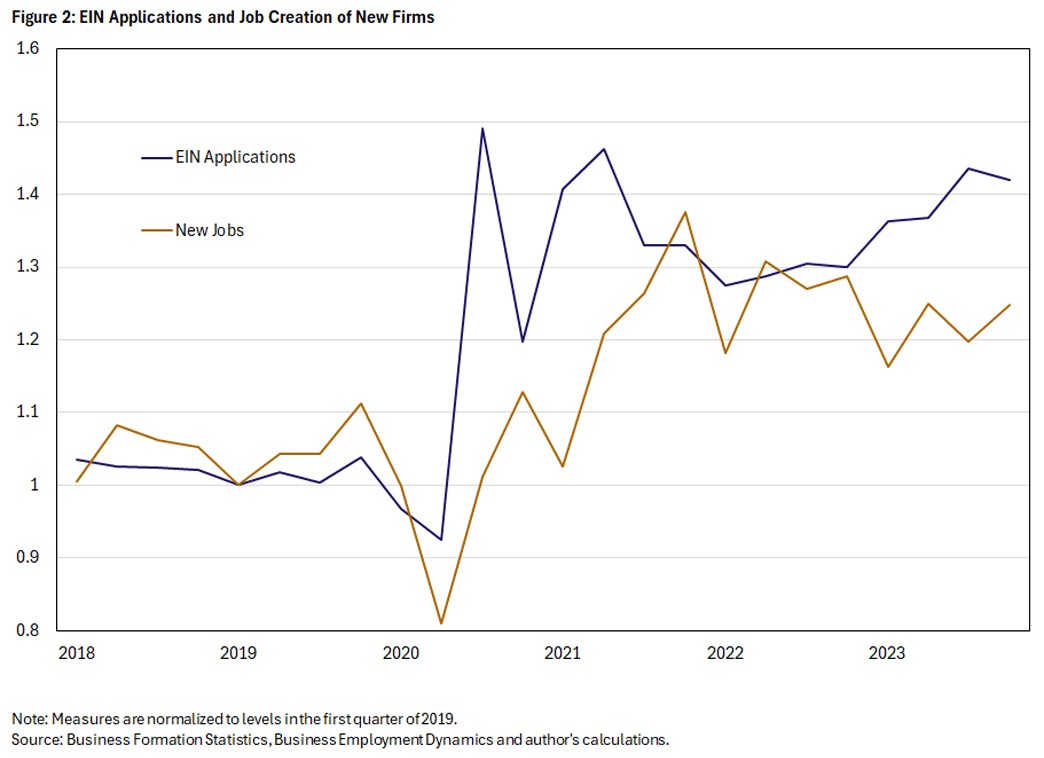

The pandemic featured historical levels of unemployment, so the rise in establishment openings and associated job creation created a more-than-welcome boost to the U.S. economy. Even though EIN applications have remained elevated (even relative to longer-run trends), employer activity by entrants has cooled significantly since its peak in late 2021. In fact, there are increasing signs that establishment openings and entrant job creation are reverting to prepandemic trends, indicating that the pandemic surge in employer activity was only a temporary phenomenon. Figure 2 shows the differing trends in EIN applications and job creation by new firms, with job creation sliding from its pandemic peak.

The temporary nature of the pandemic surge has two sides. For one, establishment openings and entrant job creation are both slowing down significantly. In fact, since peaking in late 2021, establishment openings have been falling steadily.

For another, many establishments opening during the pandemic seemed to have closed within the same year. To investigate, we will also look at the Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics (BDS) data, which tracks employer business activity at an annual frequency, specifically in March each year.

As previously discussed, the quarterly BED data indicate that establishment openings increased rapidly after the pandemic. According to the BDS, however, the rise in establishment openings is significantly milder at 15 percent, as shown in Figure 3. While this difference could be due to the Census Bureau and BLS maintaining slightly different definitions for what constitutes an establishment, a more likely explanation is that many businesses did not make it a full year, implying these specific employers are not picked up in the BDS data. For example, a business that opens in June but closes six months later will not be registered by the BDS since it only reflects a March snapshot of calendar years.

While a postpandemic increase in business formation activity obviously boosts optimism about the U.S. economy, it is important to be cautious about this buoyancy. Multiple data sources indicate that the acceleration in business formation is not that robust.

Nevertheless, levels in new employer activity are still higher than before the pandemic. The questions are whether these heightened levels can be sustained and, importantly, can they be attributed to the pandemic effect on individuals’ entrepreneurial incentives. It appears that there was already a reversal in the trend of establishment openings since mid-2009 which has persisted until the present. There seem to be strong signals that the pandemic surge was temporary and that establishment openings are simply reverting to their prepandemic trend. An identical argument can be made for entrant job creation.

The evidence is even more apparent when considering the establishment entry rate, or the number of establishment openings relative to the total number of employer establishments. This measure might better reflect entrepreneurial activity since establishments have been consistently growing recently. Similar to establishment openings, the entry rate has displayed a positive trend since late 2009, and it has basically reverted to this prepandemic positive trend. Figures 5a and 5b shows these reversions to prepandemic trends for both EIN applications of likely employers and the entry rate.

Job creation by firm entrants follows a similar pattern, as seen in Figure 6. The pandemic-era spike in job creation has been falling but seemingly returning to prepandemic trend.

Startup Business Surge and Its Potential Effects

Startup Business Surge and Its Potential Effects

These observations support the notion that the pandemic surge in EIN applications did lead to a significant increase in new employer activity in terms of both establishment openings and job creation. However, this rise in new employer businesses was temporary in nature, and future heightened levels of employer business formation seem more the result of a positive but less pronounced trend that started before the pandemic, rather than the immediate effect of the pandemic on entrepreneurial spirit.

The 2024 working paper “Surging Business Formation in the Pandemic: Causes and Consequences?“1 hypothesized that the pandemic surge in business formation could have two effects. One is an optimistic one in which “this surge is associated with a burst of innovation, with startups being an important component of the experimentation leading to that innovation.”

However, another is that the effects of the pandemic surge are temporary and have lower productivity gains than usual. In fact, the authors write that “this surge may reflect the type of spatial and sectoral restructuring that we have detected but only insofar as such restructuring is necessary for providing basic support activities for the changing nature of work and lifestyle [induced by the pandemic], with no broader spillovers in terms of innovation, productivity and growth.”

Based on the presented evidence, it appears that the effects of the pandemic itself point towards the latter narrative. However, this view does not preclude the idea that significant aggregate productivity gains could be realized from the positive prepandemic trend in startup activity.

Productivity Effects of Pandemic Surge in Startups

Employer startups constitute only a small fraction of the stock of aggregate employment, as it has historically been less than 3 percent. However, their contribution to aggregate job creation and productivity growth is disproportionately high. Despite their small size, employer startups have contributed about 15 percent to aggregate job creation, and some studies have shown that about 25 percent of aggregate growth can be attributed to entrants alone.2

As a result, it is worth considering whether the pandemic surge in employer startups led to significant productivity gains. While the microdata to investigate this question are not available yet, we can draw some insights from industry-level data on employment and productivity. To obtain industry-level establishment openings, we will rely on quarterly data from the BLS’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW). Surges in EIN applications were strongest in the manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, transportation and warehousing, and information and other services sectors, so we will focus on this particular subset of industries. Interestingly, there were only two industries in this set that performed better than the aggregate when it comes to entrant job creation after the pandemic: manufacturing and information. The superior performance by the information sector is particularly visible, as seen in Figure 7.

The following question is then: Did industries with strong increases in entrant job creation after the pandemic also see higher productivity growth in the past few years? Somewhat surprisingly, only one industry within this set realized significant productivity gains between 2017 and 2022: the information sector at 10.92 percent.3 Productivity gains for manufacturing are almost zero (0.06 percent), and the other industries’ productivity levels have actually fallen since 2017: Total factor productivity in the transportation and warehousing sector and the retail trade sector dropped 7.36 percent and 2.04 percent, respectively, between 2017 and 2022.4

As a result, any potential aggregate productivity gains due to the pandemic surge must likely have come from the information sector. However, the aggregate gains are likely to be small since the sector is a relatively small industry, as its shares of aggregate employment and value added are around 2.65 and 5.30 percent, respectively. Thus, it is unlikely that the pandemic surge in business formation yielded significant productivity gains from an aggregate perspective.

Conclusion

The pandemic saw unemployment levels that were unprecedented in modern history. However, the pandemic was also accompanied by a large surge in business applications, which translated into a comparable percentage increase in businesses hiring employees. This rise in establishment openings and entrant job creation was initially received with a lot of enthusiasm. The surge in employment activity by entrants seemed to persist for several quarters and appeared robust, which was a welcome boost for U.S. entrepreneurism that had been on the decline for the past few decades.

While establishment openings and job creation by entrants are still at elevated levels compared to before the pandemic, they are slowing down considerably, and some caution is warranted. In fact, it appears that these metrics for startup activity are reverting to prepandemic trends. As a result, the pandemic surge in business formation only had temporary effects, and future heightened levels of employer activity by entrants seem more the result of a positive trend that originated more than 10 years ago, rather than the immediate effect of the pandemic on entrepreneurial spirits.

Lastly, spikes in startup activity are typically associated with aggregate productivity gains. However, the pandemic surge in entrant job creation was mostly concentrated in industries characterized by low or even negative productivity growth. The exception is the information sector, which has experienced tremendous productivity growth. However, this sector is relatively small and is therefore unlikely to have had a significant impact on the aggregate. Only future data releases will reveal whether the pandemic surge in business formation truly had long-lasting effects on entrepreneurial activity and aggregate productivity (growth).

Chen Yeh is a senior economist in the Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Discussion about this post