Steely decision: On Saturday, the government recalled parliament for a rare weekend sitting to pass an emergency law to save British Steel’s Scunthorpe plant from closure, bringing it under government control and preventing the plant’s Chinese owner from shutting down the blast furnaces, which would be near-impossible to restart.

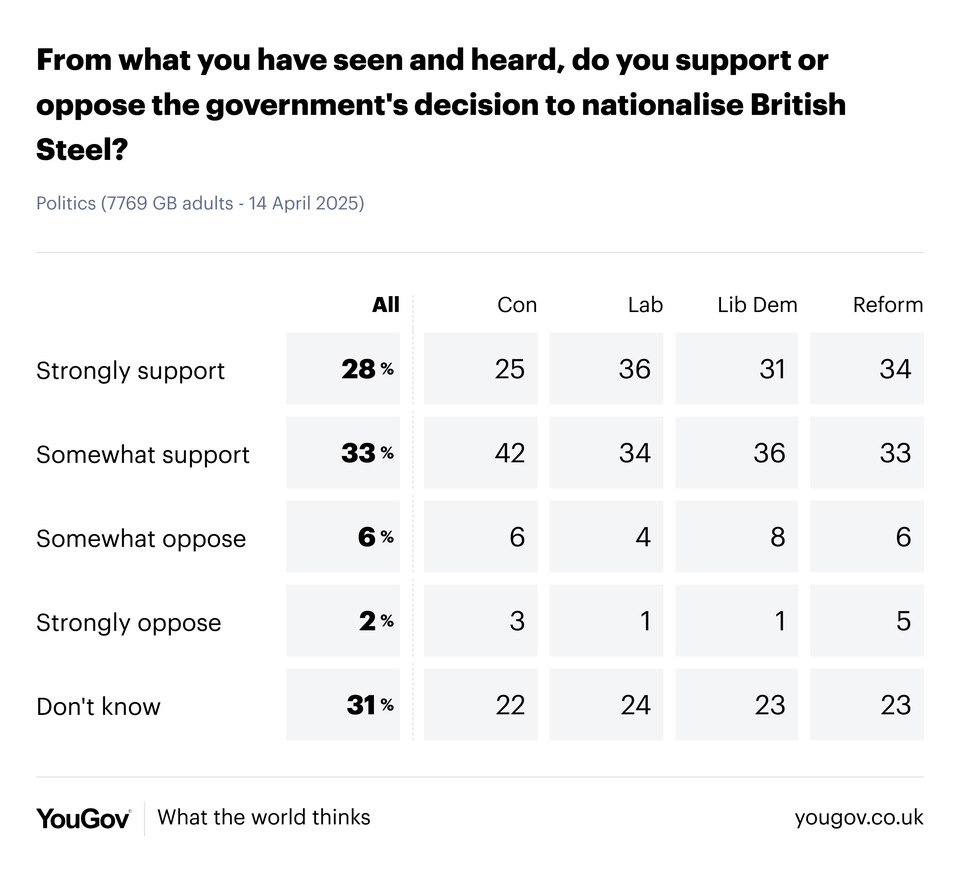

61% of Britons say they back nationalisation of British Steel, a small increase on the 57% who said so on Friday ahead of the emergency recall of parliament. Just 8% of the public are opposed to the move.

There is little disagreement among voters, with the 70% of Labour voters in favour of the effective nationalisation joined by 67% of Conservative, Lib Dem and Reform UK voters.

In a dramatic intervention to preserve a cornerstone of British industry, the U.K. government has taken emergency control of British Steel, with full nationalization emerging as the likely next step to safeguard thousands of jobs and maintain the country’s capacity to produce virgin steel. The move, which prompted a rare Saturday session of Parliament, underscores the strategic importance of steelmaking to Britain’s economy and national security, particularly amid global trade tensions and supply chain uncertainties.

The decision comes after months of fraught negotiations with British Steel’s Chinese owner, Jingye Group, which acquired the company in 2020. Facing daily losses of approximately £700,000 ($915,600) at its Scunthorpe plant, Jingye warned that the facility’s two blast furnaces—the last of their kind in the U.K.—were at risk of imminent closure due to financial pressures exacerbated by U.S. tariffs and rising raw mate

“We are stepping in to save British steel,” Mr. Starmer declared after Parliament passed emergency legislation granting Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds authority to direct the company’s operations, including ordering raw materials to keep the furnaces running. Mr. Reynolds, addressing lawmakers, described nationalization as a “likely option,” noting that Jingye had rejected substantial government offers to stabilize the plant. “Steel is fundamental to Britain’s industrial strength, to our security, and to our identity as a primary global power,” he said.

The Scunthorpe facility, which employs about 2,700 workers directly and supports thousands more in supply chains, produces steel critical for infrastructure projects, including rails for Network Rail, which sources 95% of its tracks from the plant. A closure would have ripple effects, threatening not only jobs but also Britain’s ability to meet defense and construction needs independently. As one industry leader posted on X, “British Steel’s collapse would be a body blow to U.K. manufacturing. Nationalization isn’t ideal, but losing this capacity is unthinkable.”

The crisis has been building for months. Last year, talks between the government and Jingye over a £500 million support package to transition to greener electric arc furnaces faltered, with Jingye citing unsustainable costs and demanding greater investment. The reimposition of a 25% U.S. tariff on steel imports by President Donald J. Trump further strained the company’s finances, echoing concerns raised by unions about the vulnerability of British industry to global market shifts. “The government had no choice but to act,” said a Whitehall source familiar with the discussions. “Letting Scunthorpe go would’ve cost the economy over £1 billion—more than keeping it alive.”

Public sentiment, as reflected on platforms like X, has been mixed but largely supportive of the government’s intervention. One user, @walshi01, posted, “Maybe Labour can do something right! British Steel set to be nationalized to save UK jobs, economy, and security.” Others expressed skepticism about the long-term viability of state ownership, with @A51FR3D noting, “Nationalization might buy time, but what’s the plan to make it profitable?” Such concerns recall Britain’s past experiments with steel nationalization, notably in 1967, when the British Steel Corporation was formed, only to face inefficiencies before privatization under Margaret Thatcher in 1988.

Trade unions, a powerful voice in the debate, have championed nationalization as the only path to preserve jobs and industrial capability. The GMB union called the government’s move “the first step in the process” to save the steel industry, while Unite’s general secretary, Sharon Graham, argued that steel should be designated critical infrastructure. “The government being an investor of first resort is an important first step,” she said in a statement.

Yet the decision has not been without critics. Some opposition MPs, particularly from regions like Wales and Scotland, where steel plants like Port Talbot and Grangemouth have faced closures without similar interventions, accused the government of inconsistency. “The people of Wales won’t forget that Port Talbot was allowed to lose its blast furnaces,” a Plaid Cymru spokesperson said. Others, including Conservative MPs, warned of the financial burden on taxpayers, though several, alongside Reform UK’s Nigel Farage, backed nationalization as a last resort to protect national interests.

The government’s immediate priority is securing raw materials to keep Scunthorpe operational, with more than a dozen businesses reportedly offering assistance. Mr. Reynolds has signaled openness to private-sector partnerships to reduce the state’s long-term role, but he emphasized that “a failure to act today would prevent any more desirable outcome.” The cost of sustaining the plant remains a concern, with estimates suggesting losses could strain the government’s £2.5 billion steel fund.

For now, the emergency powers mark a bold assertion of state responsibility for an industry that has shaped Britain’s industrial identity since the 19th century. As the government navigates the complexities of nationalization, the fate of British Steel will test Labour’s pledge to revitalize manufacturing while balancing economic realities in an uncertain global landscape.

Discussion about this post