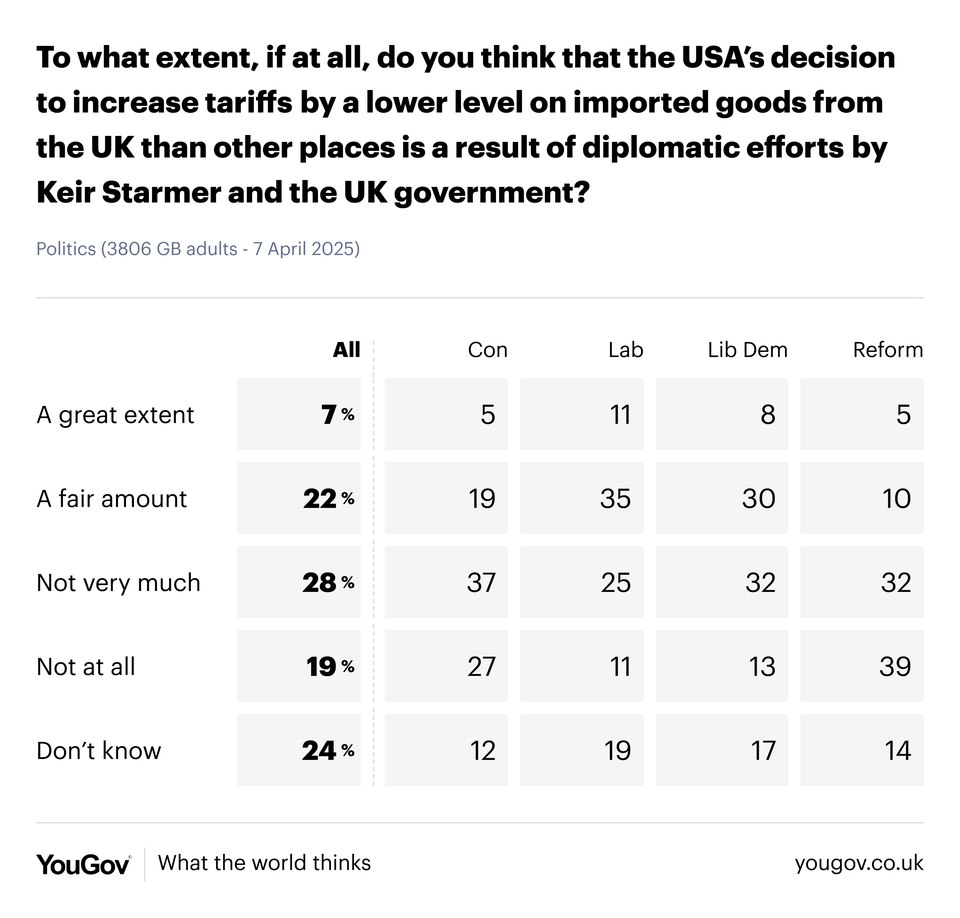

Tariffs: With the US imposing new tariff rates on dozens of countries last week, the UK was subject to one of the lowest increases, at a rate of 10% compared to 20% for the EU and 34% for China. The government appear to want to present this as a success for recent British diplomatic efforts, but in reality it appears that the UK’s rate – and everyone else’s – was based on a specific formula. Indeed, almost half of Britons (47%) believe that diplomatic efforts by Starmer and the wider government made little to no difference on the tariff rate the UK was given, with only 29% thinking the efforts made a great or fair amount of difference.

Labour voters are the group most likely to think British diplomacy made much of a difference, with 46% saying so compared to 38% of Lib Dems, 24% of Tories and 15% of Reform UK voters

The United Kingdom’s economy enters the spring of 2025 grappling with sluggish growth, high public debt, and an uncertain global trade environment, vulnerabilities that could be tested by shifting international pressures. After years of post-Brexit adjustment and inflationary shocks, Britain stands at a crossroads, with its fiscal resilience under scrutiny and its trade relationships poised for potential upheaval.

Official data paints a sobering picture. The Office for National Statistics reported GDP growth of just 0.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2024, reflecting a near-stagnant economy battered by high energy costs and weak consumer spending. Public debt, hovering near 100 percent of GDP according to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), limits the government’s ability to respond to new shocks. Inflation, though eased from its 2022 peak of 11.1 percent, remained at 2.6 percent in February 2025, above the Bank of England’s 2 percent target, prompting the central bank to hold interest rates at 4.75 percent in its latest meeting.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s Labour government, in power since July 2024, has prioritized economic stabilization. Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ October 2024 budget raised taxes by £40 billion—targeting businesses and high earners—to fund public services while pledging fiscal discipline. Yet the OBR warned that this left only £9.9 billion in headroom against her borrowing rules, a buffer that could vanish with unexpected disruptions. “The economy is on a knife-edge,” said Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, in a November 2024 analysis. “Any external jolt could force tough choices.”

Trade, a linchpin of Britain’s post-Brexit strategy, remains a wildcard. The U.S., the UK’s largest single-country export market, accounted for £178 billion in goods and services trade in 2023, per the Department for Business and Trade. Industries like automotive and pharmaceuticals—reliant on American demand—face ongoing risks from potential policy shifts under President Donald Trump, who returned to office in January 2025. While no new tariffs have been implemented as of this writing, Trump’s campaign rhetoric promising aggressive trade measures has stoked unease.

A December 2024 report from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research cautioned that a 10 percent U.S. tariff could shave 0.5 percent off UK GDP within two years.

Businesses are feeling the strain. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders reported a 1.2 percent drop in car production in 2024, with exports to the U.S. softening amid uncertainty. Pharmaceutical giants like AstraZeneca, which derives 40 percent of its revenue from the U.S., have flagged rising costs as a concern. “Global supply chains are fragile,” said Ruth Gregory, an economist at Capital Economics, in a January 2025 note. “Any disruption could hit the UK harder than most.”

The Bank of England’s cautious stance reflects these headwinds. Governor Andrew Bailey, speaking in March 2025, signaled openness to rate cuts if inflation subsided but warned of “upside risks” from global factors. Markets, however, are jittery—the FTSE 100 has traded flat in 2025, underperforming European peers, as investors weigh Britain’s exposure.

Starmer’s government is banking on diplomacy to bolster trade ties, particularly with the U.S. and EU, where a reset in relations has yielded modest progress. Yet analysts see limits to this approach. “The UK’s leverage is constrained,” said Thomas Wright of the Brookings Institution in a February 2025 podcast. “It’s a mid-sized economy in a world of giants.”

For now, Britain’s outlook hinges on avoiding new shocks. A stable global trade environment could allow Reeves’ fiscal plans to take root, potentially lifting growth to the OBR’s projected 1.5 percent by 2026. But with debt high, buffers thin, and international tensions simmering, the UK remains a nation on edge—its economic fate tied as much to Washington and Brussels as to Westminster.

Discussion about this post