Structural inequality, family stress put African American youth at risk for elevated depressive symptoms

Growing up can be hard.

But for African American adolescents living under the poverty line, it’s even harder. Faced with challenges like food and housing insecurity and community crime, these disadvantages can affect almost every aspect of their development.

New research from the University of Georgia suggests that the stress from economic hardship may also harm youths’ mental health. But learning more about the issues that perpetuate poverty and poor mental health could help policymakers break the cycle.

“Rural African American families, in particular, contend with a social context where poverty and related challenges are extensive, a product of the ongoing effects of institutional racism and the historical legacy of slavery in this region,” said Ava Reck, lead author of the study and a doctoral student in Human Development and Family Science and the Center for Family Research. “It is critical to research youth development in challenging social contexts so that we can understand how best to support vulnerable young people.”

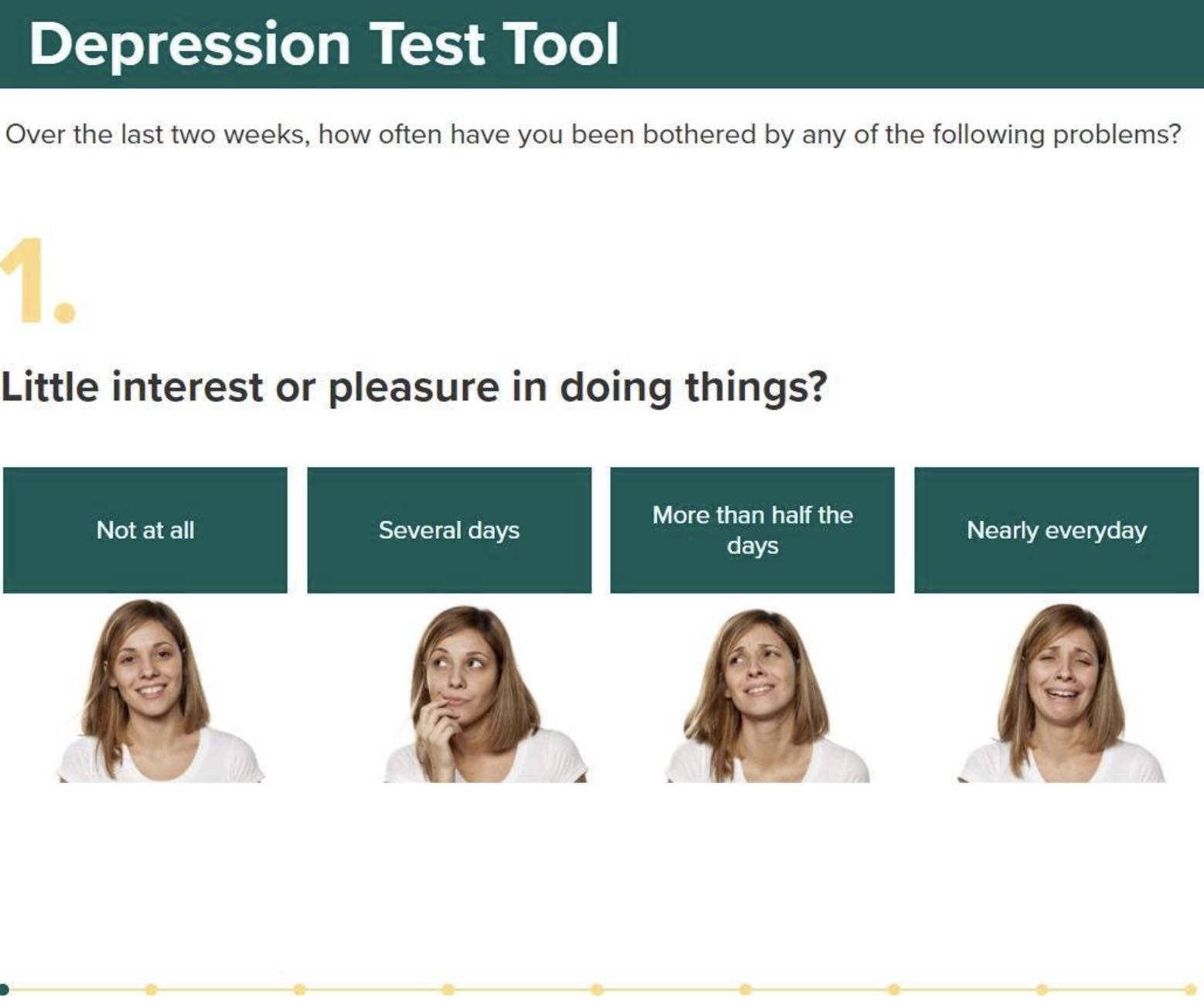

Do I have depression? Take an Online Self-Test

Depressive symptoms common

Published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, Reck’s study followed 472 African American families over the course of four years, starting when the children were 11 years old. Visiting the families in their homes once each year, the research team asked participants to complete detailed surveys on their lives, asking about everything from their personal struggles and stress to their mental health.

Rates of depressive symptoms in the study were alarming. More than half of the youth and 45% of caregivers in the study had elevated depressive symptoms, including feelings of sadness, hopelessness and loss of interest in usual activities.

For even the most dedicated and caring caregivers, high levels of stress can make parenting children in general—and parenting adolescents, in particular—so difficult. Our question now is how do we develop programs and policies to mitigate these challenges.” — Ava Reck, lead author

Reck found that socioeconomic and other family stressors undermined how family members got along with each other. In particular, family stress was linked to increases in arguing and unresolved conflict between parents and youth. This led to youth reporting greater difficulties in regulating their behavior and emotions, a precursor to depression.

“For even the most dedicated and caring caregivers, high levels of stress can make parenting children in general—and parenting adolescents, in particular—so difficult,” Reck said. “Our question now is how do we develop programs and policies to mitigate these challenges of disproportionate exposure to family stress and continue moving research forward that addresses how stress impacts family functioning and youth well-being.”

Family-centered interventions

Family-centered programs are a start. And UGA research is leading the way.

The Strong African American Families Teen (SAAF-T) program was developed over a decade ago by UGA professors Gene Brody and Steve Kogan at the Center for Family Research. Groups of families meet weekly for two-hour sessions over the course of five weeks. The curriculum focuses on enhancing family relationships while preventing risky behavior. SAAF-T was shown to reduce depression among youth, conduct problems and substance use issues by more than 30%.

“In addition to family programs, we need to be serious about addressing the underlying pervasive inequalities that have dominated U.S. history,” Reck said. “Then we need to address the processes in which poverty-related stress is impacting young people’s lives. We can do that through interventions and policies that work to reduce racial inequalities, reduce family stress, improve parent-youth relationships and help youth regulate their emotions. We also need culturally competent mental health care for Black adolescents.”

As for what we can do in the meantime, parents and caregivers can practice involved, vigilant parenting by giving their adolescents limits and expectations, with a lot of warmth and open communication.

“Adolescence can be a challenging time,” Reck said. “Conflict can be hard to avoid. But conflict might be amplified because of other stressors. We need to find ways to draw the line between how we experience stress and our feelings and behaviors in relationships. Many effective families focus on being united as a team to take on external stressors.”

This study was co-authored by Steven Kogan, the Georgia Athletic Association Professor of Human Development in the College of Family and Consumer Sciences, and was sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

by Leigh Beeson

Discussion about this post